CH 1 Introduction

Neurological and psychiatric disease represent a significant societal burden in both advanced and developing countries (Collins et al. 2011) and there is a significant need for more effective treatments. Recent advances in brain stimulation and recording technology have enabled development of long-desired treatment options for many of these diseases in the form of implantable devices that directly stimulate populations of neurons. Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is one such implantable device wherein patients receive electrical pulses via electrodes that have been implanted in the brain to mitigate their disease symptoms. DBS has become an established therapy for movement disorders (Parkinson’s Disease (PD) and essential tremor) (Perlmutter and Mink 2006) as well as epilepsy and psychiatric diseases (Holtzheimer and Mayberg 2011). Another group of implantable neurostimulators are neural prosthetics, such as cortical prostheses, which aim to restore sight in patients with congenital or acquired blindness. The body of work presented here makes progress on two unsolved challenges limiting advances in implantable neurostimulators, namely DBS state detection and more accurate cortical encoding of visual stimuli.

1.1 Deep Brain Stimulation

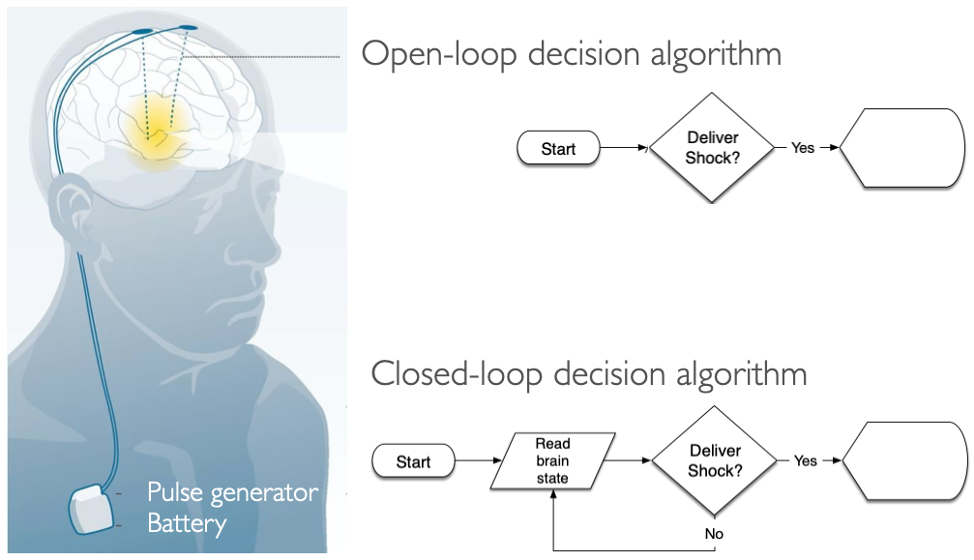

DBS uses a surgically implanted stimulator to apply electrical pulses directly to the brain to mitigate symptoms of neurologic and psychiatric diseases. Historically, drugs have been the primary method of treating these diseases, but DBS has emerged as a promising alternative for patients who do not respond to pharmacotherapy. Parkinson’s disease (PD) was among the first FDA approved uses of DBS for mitigating the disease’s motor symptoms. When employed for treating PD, current best practice for DBS therapy uses constant stimulation even though its therapeutic benefits to motor symptoms are only needed when the patient is awake and trying to move (Fig 1.1). Current implanted stimulators are used this way because they have no way to detect when stimulation is not needed, such as when the patient is asleep or when lower levels of stimulation are needed to correct resting tremor. This strategy of constant stimulation, or open-loop stimulation, is less power efficient and comes with side effects such as impaired cognition, speech, gait, and balance (Hariz et al. 2008). However, activating DBS stimulation only when necessary requires a robust method for discerning whether or not the patient’s brain needs stimulation. For example, a closed-loop DBS system would read out the patient’s brain state and only deliver electrical pulses during periods when the patient is awake. Closed-loop DBS is more power efficient and would have less collateral side effects by only stimulating when necessary.

Figure 1.1: Closed-loop DBS system would read out the patient’s brain state to modulate stimulation intensity accordingly based on if the patient is awake, stationary, or moving

1.2 Neural Interfaces

Cortical prosthetics (Fig 2) are a form of neural interface used to restore sight in blind patients (Lorach et al. 2013). These implantable neurostimulators bypass lost or damaged neurons by stimulating the damaged neurons targets the same way the original neurons otherwise would. Cortical prostheses must reproduce the neural activity patterns that would typically be relayed naturally by neurons of the thalamic lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) and retina when directly stimulating visual cortex. Neural encoding, our understanding of how neurons reformat and represent visual stimuli, is key to this goal of properly restoring sight.Unfortunately, current models of neural encoding still struggle to accurately predict neuron responses to natural images stimuli.

1.2.1 Bottom-up neural encoding models

The ultimate test of our knowledge of neural encoding is to predict neural responses to stimuli. For instance, we know the visual cortex receives complex spatiotemporal patterns of light relayed by the retina and reformats these patterns to infer what caused them (i.e. the identity of the object).

A neuron’s receptive field (RF) depicts the properties of an image that modulate the neurons activity. RF’s are typically represented in models by linear filters applied at the first stage of processing. The inner product (i.e. dot product) between the filter and corresponding image region predict a given neurons response to that image. The linear RF model was insufficient for predicting several non-linear properties of RGC responses to white noise. Linear-Nonlinear-Poisson (LNP) (Paninski et al., 2004) models are commonly used to predict RGC spike rates in responses to image stimuli. LNP combines a linear spatial filter with a single static non-linearity. The LNP model predicts neural responses well for white noise stimuli but does not generalize well when used to predict responses to natural image stimuli. Generalized Linear Model’s (GLM) (Pillow et al., 2008) improve prediction accuracy by accounting for interactions between RGC’s and substituting the spatial receptive field with a spatiotemporal receptive field.

1.2.2 Top-down neural encoding models

The genome likely has insufficient capacity for specifying every neuronal connection (synapse) (Zador, 2019) so what mechanisms ensure that neurons are connected correctly? This has recently been referred to as the “brain wiring problem” (Hassan and Hiesinger, 2015). We’ll be looking specifically at how synaptic wiring is determined in visual cortex. Before the eyes even open, molecular interactions and spontaneous activity of retinal ganglion cells (RGC’s) guide development of the initial “coarse” connectivity between retinal ganglion cells in the eye, neurons of the LGN and primary visual cortex (V1) (Del Rio and Feller, 2006; Katz and Shatz, 1996). After this retinotopic map is established, synaptic connectivity continues refinement but requires environmental stimuli (Pietro Berkes et al., 2011). Identifying this “unifying principle” or computational goal that guides stimuli-dependent refinement of connectivity would help explain the structure of visual representations in V1 and beyond.

1.2.2.1 Sparse coding

Shortly after the discovery of simple and complex cells (Hubel and Wiesel, 1959), Horace Barlow proposed efficient coding (Barlow, 1961) as an explanation for the computations performed by neural circuits in sensory cortex. The efficient coding hypothesis posits that the overarching goal of sensory processing is to reduce the high information redundancy in stimuli from the physical environment. This view was strengthened by findings that the Gabor-like receptive fields of simple cells are an optimal basis set for natural scenes when optimizing for 1) representation sparsity and 2) image reconstruction (D. Field, 1987; Olshausen and D. J. Field, 1996). Due to the highly metabolic nature of neurons, sparse coding was proposed as an alternative goal which has the added benefit of being metabolically and information efficient (Levy and Baxter, 1996). Sparse coding models were particularly influential after successfully predicting aspects of neural computations in retina (Atick and Redlich, 1992), thalamus (Dan et al., 1996) and V1 (Olshausen and D. J. Field, 1996).

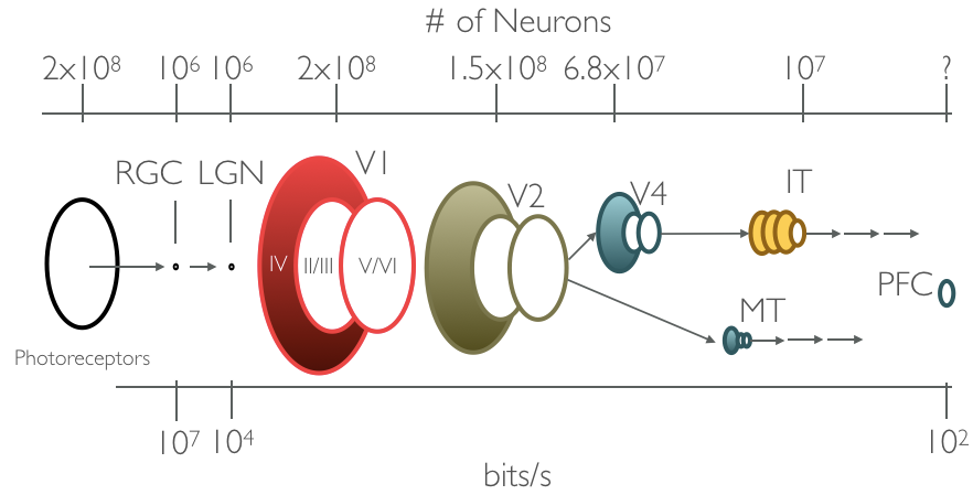

Optimizing for efficient coding would predict information redundancy should decrease as it is processed and relayed by successive visual areas. Information redundancy decreases when the same information can be carried by fewer neurons, which occurs as visual information propagates from photoreceptors to RGC and from retinal ganglion cells to cells of area LGN (Figure 1.2). Instead of information redundancy decreasing, as would be predicted by efficient coding, anatomical evidence seems to indicate that information redundancy in primary visual cortex is likely higher than it is prior areas of visual processing (Felleman and Van Essen 1991, @Barlow:2001ub). Furthermore, despite some modest successes at explaining the complex response properties of V2 (the next visual area after V1) (Lee, Ekanadham, and Ng 2008, @Olshausen:2001we) subsequent findings (Berkes, White, and Fiser 2009, @Willmore:2011ks) have shown that subsequent visual areas beyond V2 cannot be explained by the efficient coding hypothesis. Efficient coding alone as an objective is not sufficient for explaining response properties of neurons in higher level visual areas like V4 and inferior temporal cortex (IT).

Figure 1.2: Channel capacity, the number of neurons carrying visual information, significantly varies along the ventral visual stream

1.2.2.2 Goal-directed convolutional neural networks

Barlow, when reflecting later on his original idea (Barlow, 2001) makes a prescient statement, perhaps without knowing it: “We now need to step back and take a more global view of the brain’s task in order to see what lies behind the importance of recognizing redundancy”. Neural networks which optimize behaviorally relevant tasks (Yamins and DiCarlo 2016) have shown state of the art performance at predicting neuronal activity across the ventral visual stream.

1.3 Summary

Chapter 2 provides an introduction to artificial neural networks, their similarities and differences to biological neurons, and the machine learning techniques used to train them which serves as a foundation for the technical chapters that follow.

In Chapter 3 we demonstrate ANN models as a tool for decoding sleep state in real-time using only the signals available from intracranial DBS electrodes implanted in the basal ganglia of PD patients. Importantly, this model generalizes decoding to patients never seen by the model and may allow new ways to leverage implantable stimulators for therapeutic benefit.

Chapter 4 explores how neural networks can be used as a tool for explaining the overarching goals of neural encoding in ventral stream visual processing. This work was motivated by the observation that visual processing areas are reactivated during visualization tasks indicating their dual role in visual processing and regenerating stimuli.

Finally, Chapter 5 demonstrates the utility of neural network models as a way to explain response properties of individual neurons. We use a convolutional neural network (CNN) to achieve performance comparable to state of the art at predicting activity of individual neurons evoked by natural image stimuli in macaque V1. Furthermore, we use this model generatively to explain response properties of cells outside of Hubel and Wiesel’s simple- or complex-cell designations.